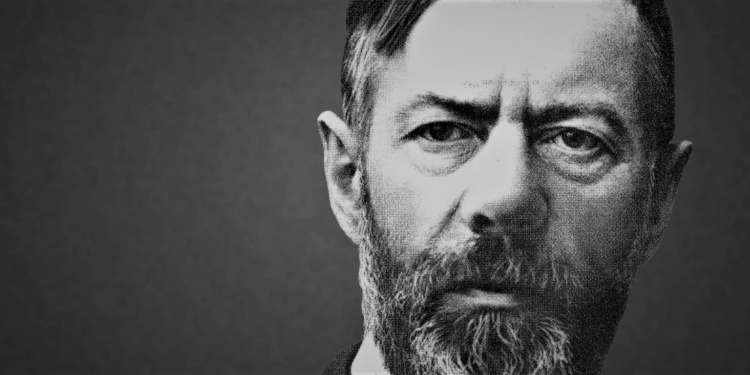

Image: OECD Secretary-General Mathias Cormann accepts the glass key symbolising the handover from outgoing Secretary-General Gurria, helped by Prime Minister Bettel. Source: OECD.

‘TIS THE SEASON of top-level appointments in international organizations. António Guterres has just secured a second mandate to head the United Nations (UN). But across the board, quiet diplomacy is doing its steady work: New Secretaries-General, Directors-General, Deputies-Director, and more, are being sworn into the international system.

Rebeca Grynspan took over the UN’s Conference on Trade and Development, as the first woman and first Central American to hold the top job. At the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, Mathias Cormann took office earlier this month after being handed over the symbolic glass key (see picture) of the organization.

All things considered, ours are tough times to be entering the multilateral arena. The world is undergoing transformational change at all levels, and crises abound. Looking at executive heads, old and new, handing down symbolic keys, one also wants to believe that he (or she) who holds the key is also the key to many of our current predicaments.

So, what can one or another Secretary-General do? What is the extent of their influence? What makes one individual a good candidate for the highest office?

“If we want to answer the question ‘Are international organizations merely the instruments of national foreign policies or do they influence world politics in their own right?’ then we must take a closer look at the executive head,” wrote Robert W. Cox.

What scholars call the great-man theory of international organization consists of looking at interpersonal and cross-cultural skills as good indicators of future performance on the executive level.

There are charismatic types and bureaucratic types. Classic leaders like the International Labor Organization’s Albert Thomas “infused his staff with a sense of devotion to a cause of which he appeared to them as a world leader,” writes one scholar. Others, such as the World Bank’s A. W. Clausen, were dogged pragmatists and effective managers, says another.

The UN’s Dag Hammarskjöld is not only remembered for his tragic death but also his clarity of spirit, as a key agent in solving the Suez crisis in 1956. In a letter to a personal friend, he wrote: “If, as in the Suez situation, the very facts, as established by the policy of the various big powers, force the Secretary-General into a key role, I am perfectly willing to risk being a political casualty if there is an outside chance of achieving positive results.”

Beyond individual characteristics, an executive head must be on the edge of his time, willing to seize opportunities and to bring out positive results while having enough wisdom to identify these opportunities in the first place. For this reason, a leader’s capacity to act is strongly determined by the current state of the global-political scene. In a fractured world, leaders have a responsibility to build and maintain consensus among squabbling nations. Proposed courses of action must appear less harmful than continued confrontation.

Like the sailor, world leaders must leverage the winds of the day to advance a universal agenda. And like the spider, they must spin a web of alliances both inside and outside international organizations that enables and pushes forward the common good’s rightful cause.

In his most recent oath of office, António Guterres reminds us that “our greatest challenges” are also “our greatest opportunities.” Though he spoke in the first-person plural because no one achieves anything alone, it is useful to be reminded that the Secretary-General as an individual is instrumental in carrying out the vision he set forth for the organization.

As famously stated by Loveday, “there is no a priori reason for assuming that the head of an international organization will prove competent and judicious,” for their selection process is not only meritocratic but also intensely political. History will tell if, echoing great figures of the past, today’s leaders will succeed at turning great challenges into great opportunities. But may that not stop us from remaining optimistic.

Author

-

Murillo Salvador is chief editor at International-Organization.Com. In the past, he has worked at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and at the Mission of Brazil to the World Trade Organization. He currently lives in Geneva.

View all posts

Related Articles

May 17, 2021

Revisiting Weber’s Spirit of Capitalism

The world must live up to tough challenges today, and the study of collective ethics under capitalism has never been more relevant. To that end, the work of Max Weber can still guide our reflection.

April 26, 2021

Grasping Malfunctional International Organizations

In a world of bad news, it can be tempting to point fingers and deflect blame. How can we make sense of the crisis of multilateralism in a context where confusion is so pervasive?

April 5, 2021

On Fear of Terminal Decline

The problem with “declinism” is that it can impoverish our imaginations by luring us to the sirens of either total change or fatalism. On this topic, thinker Albert Hirschman is notably savvy.