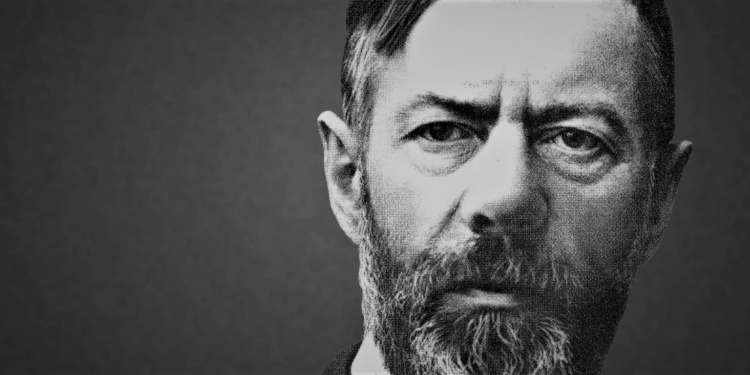

Image: French sociologist Michel Crozier, 1992. Source: Andersen/SIPA.

THE DECADE OF 1960 had seen its fair share of activity at the height of the Cold War. From the elevation of the Berlin Wall, the Cuban missile crisis, an unsettling escalation of the nuclear arms race, the successful assassination of US President Kennedy, to man’s first braggart steps on the surface of the Moon. And several African countries were breaking free from centuries-old European imperialism.

In light of these events, in 1967, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, then a Geneva-based think-tank, launched a study group whose goal was to address an emerging issue of the day. Renowned scholars, most of them specializing in political science and international law, were invited to discuss the thorny matter of international organization.

Among them, Michel Crozier stood out – not for being French but, rather, a sociologist. Yet his authority on the matter was unquestioned. He had just published his showpiece The Bureaucratic Phenomenon, founded a whole new discipline on the study of organizations, and international organizations were, after all, organizations. As a matter of fact, right then and right there, years before its time, Crozier had an alluring idea.

Up front, the Frenchman asserted that “the problems of international organization cannot be solved as a mere special case of the theory of international relations.” Nor, he admitted, can they be solved as a special case of the science or sociology of organizations. Indeed, he went on, a science of international organizations requires a conceptual framework by and for itself – one capable of shedding new light on the unique “customs, conceptions, methods and values” developed by these institutions.

Fast-forward to the 1990s. Thirty years after Crozier’s contributions, such a conceptual framework was indeed being developed. Prominent academics such as Michael Barnett and Martha Finnemore strived to understand why international organizations that “are not always efficient or effective servants of their members’ interests can still exist,” among other things.

How can we grasp the permanence, resilience, and adaptation of an international organization in our current context of crisis and questioning of the multilateral system? Today, multilateralism must hold its balance in the evermore shifting grounds of 21st century’s dawning world order, and it has so-far achieved varying degrees of success.

We must keep developing the right tools that Crozier called for fifty years ago. These instruments should enable us – and as many of us as possible – a clearer understanding of what exactly is going on in the world. Outdated disciplinary boundaries must be broken up. The sacred must be desecrated and set upside-down. Thankfully, some scholars have already started doing just that.

In 2007, an unprecedented field-study of the World Trade Organization (WTO) led a group of anthropologists, chief among them Marc Abélès, towards several insights that are decidedly still useful today. According to them, the task ahead consists in improving our understanding of the global-political scene.

As a by-product of neoliberal globalization, the global-political scene is the place where – “among constellations of international organizations and other actors that have been emancipated from the purely territorial governance of a nation-state” – an unparalleled management of the most pernicious problems of humanity is now being instituted: dealing with financial crises, world health, education policies, hunger and poverty, income inequalities, terrorism, ecological sustainability, and more.

In such an environment, international organizations propose sometimes competing models of governance and regulation. The WTO, for instance, says Abélès, poses itself as a “lesser evil” in the face of “the arbitrariness of the market, which risks destabilizing national economies much more profoundly.”

It is important, from an organizational perspective, to understand the role and place of an international body within the global-political scene. That is not necessarily a matter of assessing the former’s ability to achieve some arcane objectives, or to fulfil a legal mandate – which would rather be a matter for international relations and law scholars.

After all, proclaimed objectives are often vague, contradictory, and can lead to teleological reasoning. A sound assessment of these objectives is not always possible. Worse, such a goal-based perspective inevitably leads one to take sides in the normative relationship between developing countries and international organizations, as prominent scholar Robert W. Cox once pointed out.

We must also recognize that objectives are constantly changing, and so are their relative orders of priority among the various organizations with overlapping mandates that inhabit the global-political scene. Indeed, one must distinguish slogans – such as “promoting free trade” – from real political processes of international integration and organization.

Going back to Crozier, our aim is rather to better understand “the latent function that the participation of member nations in a common enterprise necessarily implies.” We need to examine the degree to which an international organization’s activity within the global-political scene consists in an active process of institutionalization of its policy-area, for example.

How does one make a group of countries transition from a system of contention to a system of organized cooperation? Or, as scholars Barbara Levitt and James G. March put it: How does an organization manage to reconcile its members’ inconsistent objectives in the name of the need to act on behalf of a single objective?

All in all, we must be aware of the various existing degrees of organization that exist today. We must also decide how far we want to go, in Crozier’s own words, “from a system of relations whose regulation remains implicit and imperceptible for its members, through a system in which the elements of regulation are accepted and recognized as such, and finally to a system capable of taking decisions itself, in terms of regulation.”

The science of international organization is still developing, of course. But it is growing fast. And Crozier’s long echo must remain a guiding principle for any – including this publication – participant in this open discussion.

Author

-

Murillo Salvador is chief editor at International-Organization.Com. In the past, he has worked at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and at the Mission of Brazil to the World Trade Organization. He currently lives in Geneva.

View all posts

Related Articles

June 21, 2021

Changing Hands

Leading an international organization is a tough job. But it is also full of potential: The individual characteristics of the executive head can make or break international cooperation.

May 17, 2021

Revisiting Weber’s Spirit of Capitalism

The world must live up to tough challenges today, and the study of collective ethics under capitalism has never been more relevant. To that end, the work of Max Weber can still guide our reflection.

April 26, 2021

Grasping Malfunctional International Organizations

In a world of bad news, it can be tempting to point fingers and deflect blame. How can we make sense of the crisis of multilateralism in a context where confusion is so pervasive?